Any system that becomes the sole container for existential meaning will behave like a religion, including its pathologies.

That’s not a moral judgment. It’s a psychological observation.

We tend to talk about religion as something people either believe in or reject. But from an existential perspective, that framing misses what religion actually does. Religion isn’t primarily a set of supernatural claims. It’s a symbolic system that helps human beings orient themselves inside chaos. It answers questions we cannot avoid but cannot solve: Why am I here? What matters? How should I live? What do I do with suffering? What happens when I die?

From a Beckerian and Terror Management Theory perspective, those questions are not optional. They emerge the moment a creature becomes aware of its own impermanence. Once that awareness arrives, some form of meaning structure is required just to keep life psychologically livable. The mind does not ask first whether a worldview is true. It asks whether it works.

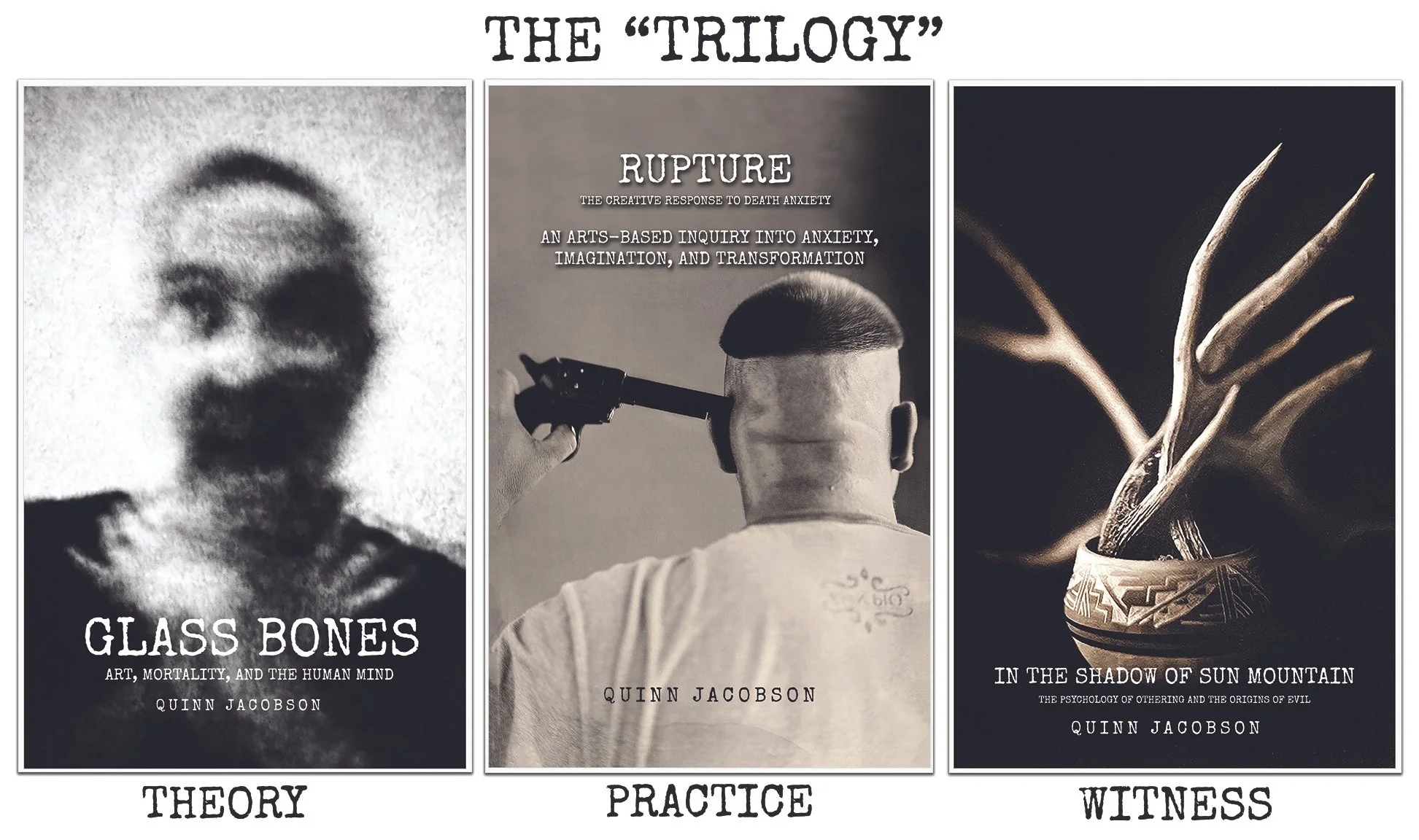

This is why the story we often tell about secularization is misleading. People haven’t outgrown religion in any deep psychological sense. What they’ve lost trust in are specific institutions. The need for meaning, belonging, ritual, and symbolic continuity hasn’t disappeared. It’s migrated.

That migration explains why so many people, particularly millennials and Gen Z, don’t experience cognitive dissonance when they abandon Christianity but embrace astrology, Tarot, wellness spirituality, social justice activism, or even technology as a source of ultimate meaning. What’s changing isn’t the need itself. It’s the container.

Institutional Christianity, for many, no longer functions as a reliable anxiety buffer. Its moral authority feels compromised. Its hierarchies often feel rigid rather than containing. Its narratives are frequently experienced as entangled with shame, coercion, exclusion, or political capture. Even when the metaphysical ideas remain compelling, the psychological cost of belonging can feel too high.

When a worldview stops regulating death anxiety at an acceptable price, it loses its grip. At that point, coherence becomes secondary. Survival takes over.

Astrology and Tarot step into that vacuum not because they are intellectually stronger systems, but because they are existentially lighter ones. They offer orientation without submission. Ritual without hierarchy. Meaning without moral surveillance. They allow uncertainty to remain open rather than demanding closure. Most importantly, they do not force a direct confrontation with mortality, judgment, or finality.

These systems operate symbolically rather than doctrinally. They don’t insist on being true in an ontological sense. They ask to be useful. A horoscope, a card pull, a full moon ritual, or a crystal doesn’t claim to explain the universe. It offers a way to relate to uncertainty without being overwhelmed by it. From a psychological standpoint, that matters more than logical consistency.

What looks like contradiction from the outside is actually an efficient substitution. The ritual structure remains. The narrative structure remains. The identity structure remains. Only the metaphysical scaffolding has softened.

The same pattern shows up elsewhere.

In transhumanist culture, technology takes on functions once reserved for God. It promises guidance, omniscience, salvation, and escape from biological limits. The language is secular, but the structure is unmistakably religious. There are messianic figures, sacred objects, and redemption narratives oriented toward immortality or cosmic significance. Death is not accepted. It is treated as a technical problem waiting to be solved.

Social justice movements can function in a similar way when they become the primary source of identity, moral orientation, and meaning. The impulse toward justice, dignity, and liberation is real and necessary. But when a movement becomes the sole container for existential meaning, it begins to develop religious characteristics: purity codes, rituals of confession, heresy boundaries, and forms of exile that replace repair. Moral failure becomes identity failure. Nuance becomes betrayal. Forgiveness becomes rare.

Again, this isn’t about whether these causes are right or wrong. It’s about structure. Any system that carries the full weight of meaning will behave like a religion, whether it admits that or not.

The danger isn’t that these new religions exist. It’s that many of them operate without the stabilizing features that older traditions developed over time: humility, elders, ritualized repair, symbolic depth, and limits on moral absolutism. Without those, belief systems become brittle. When they fracture, they tend to fracture violently inward, producing burnout, shame, or exile.

From this vantage point, secular modernity hasn’t eliminated religion. It has multiplied it. Meaning has been unbundled and redistributed across identity, politics, technology, wellness, and self-expression. The sacred hasn’t vanished. It’s fragmented.

The deeper issue is not belief, but awareness. When people insist they are “non-religious,” they often lose the ability to see how much power their chosen systems hold over them. Unacknowledged belief tends to be more rigid, not less. When meaning systems go unnamed, they can’t be examined. When they can’t be examined, they can’t mature.

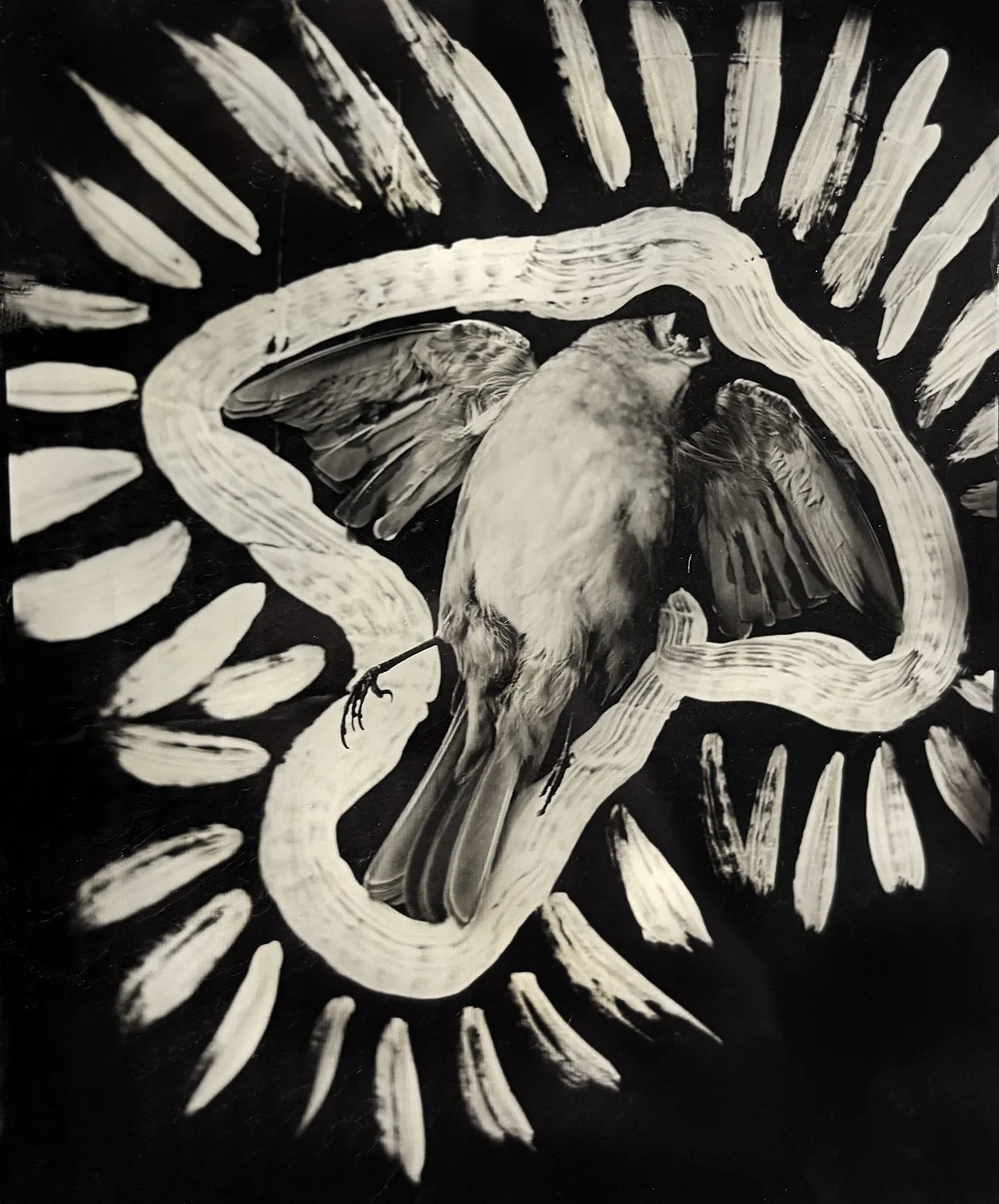

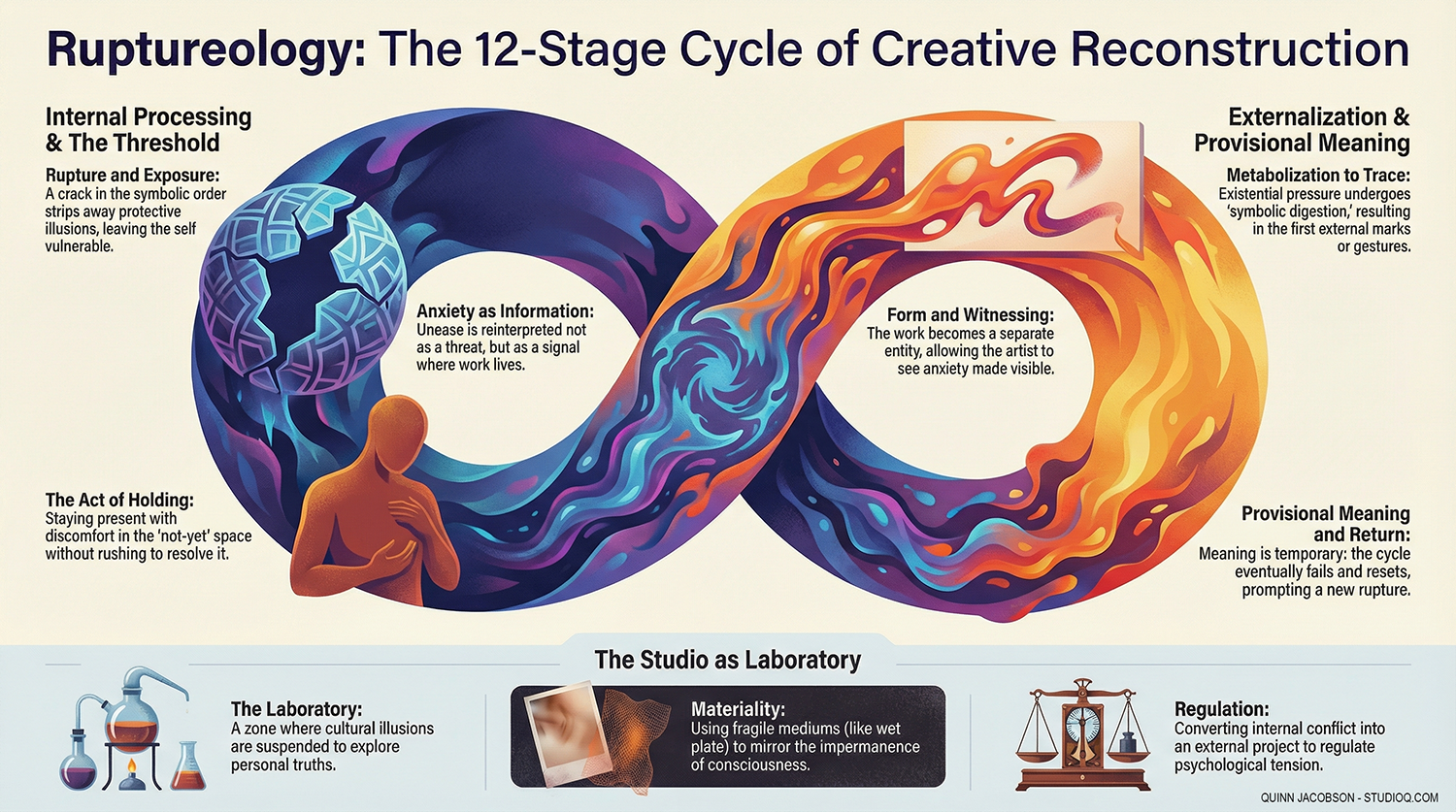

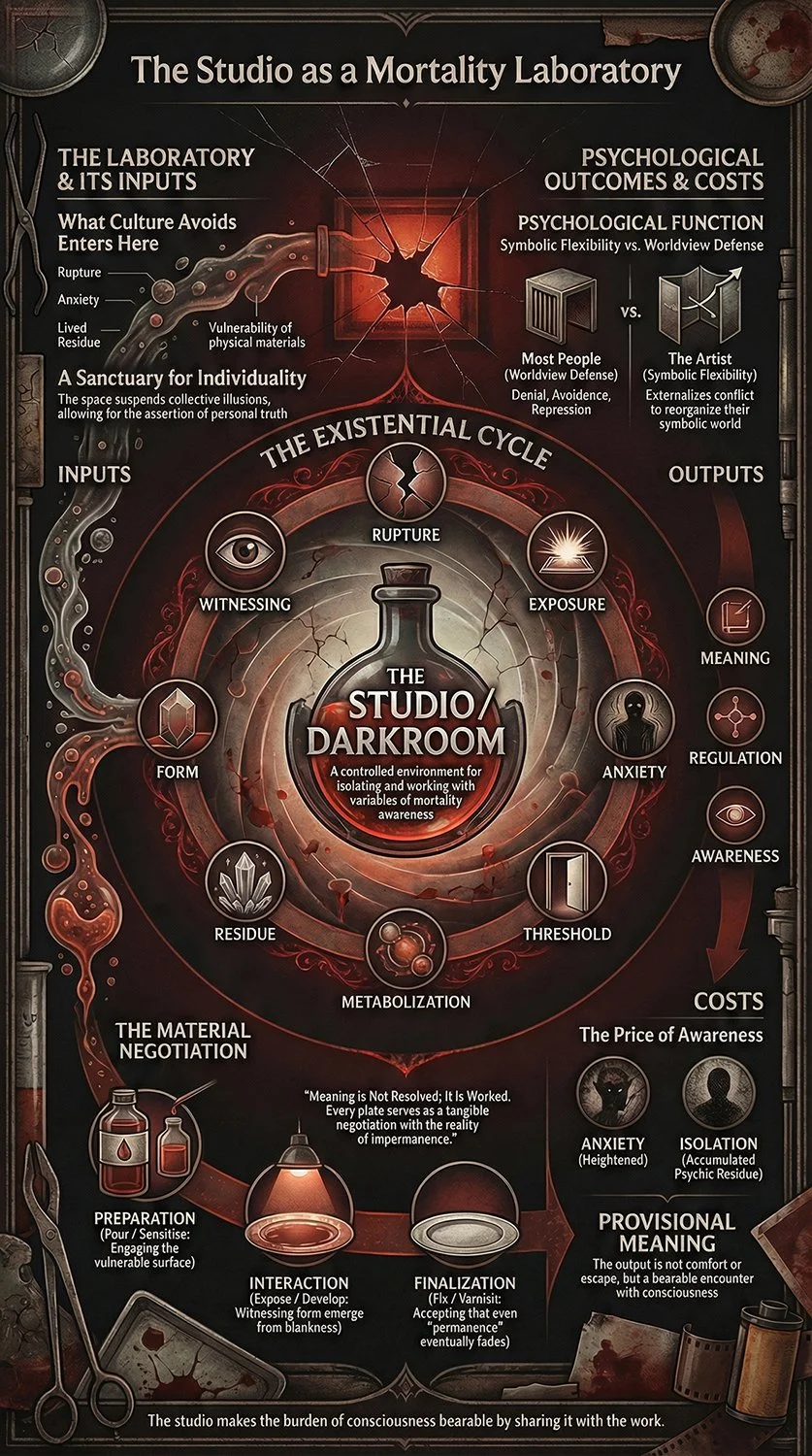

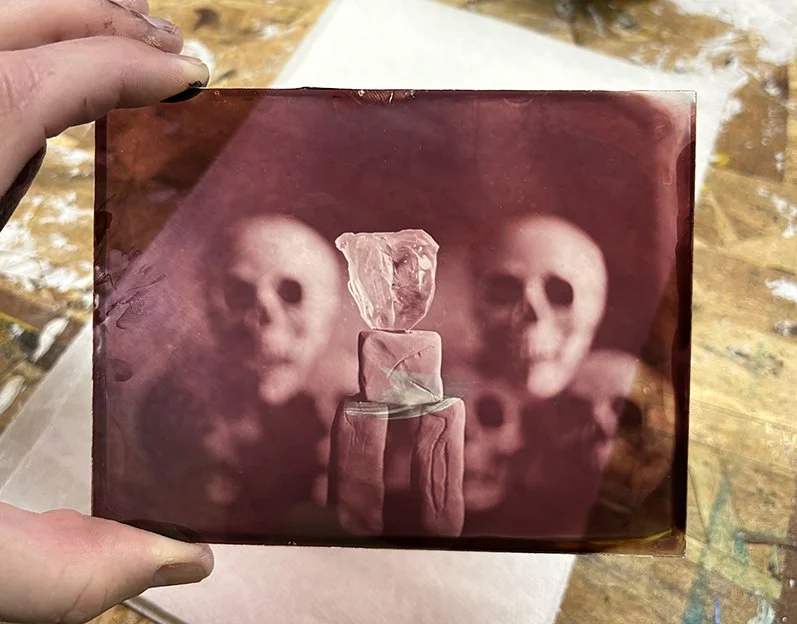

This is where artists, thinkers, and creators often occupy a strange middle ground. Creative practice can serve as a way to metabolize existential anxiety without demanding total allegiance to a single belief system. Art doesn’t promise salvation. It leaves residue. It holds ambiguity rather than resolving it. It allows meaning to emerge without pretending it will last.

In a culture struggling to live without shared containers for meaning, that matters.

The question isn’t whether you’re religious. The question is what you’re using to orient yourself inside uncertainty, suffering, and mortality. What stories you live by. What rituals you repeat. What communities you belong to. What promises keep you going when things fall apart.

Any system that becomes the sole container for existential meaning will behave like a religion.

The work, then, is not to escape belief, but to become more conscious of it.